Although a debate between the UK and EU around immigration has garnered more headlines in recent years, fishing rights are perhaps the most tangible example of why the UK wanted to leave in the first place.

Over two-thirds of the EU’s fishing waters, and two-thirds of the EU’s fishing catch, belong to Ireland and the UK. Around half of Ireland’s fishing catch take place in UK waters.

Now that the UK is leaving (and, theoretically, taking its waters with it) Ireland’s fishermen and fishing industry are under threat of being locked out of waters that had been frequented by Irish trawlers long before either country joined the EU.

As it currently stands, the UK is still in the transition period, meaning it’s still abiding by the EU fishing rules of the Common Fisheries Policy. This dictates that EU fishing fleets have access to the 6-12 nautical mile limit around each country’s coast, and neighbouring countries have access to the 0-6 mile zone.

A preliminary target date for the fisheries agreement to be struck was today, 1 July – but as of yesterday afternoon, the two sides were still debating the shape of the new fisheries arrangement to be in place between the EU and UK from next year.

These negotiations are now expected to go on for most of July and August, and possibly into the autumn. Negotiators from Brussels are hoping the UK will give EU members access to its fishing waters so that the UK can gain access to the Single Market in return.

FisheriesThis week's agenda for trade talks. Source: European Union

Patrick Murphy, CEO of the Irish South & West Fish Producers Organisation Ltd said that when Ireland first joined the EU in 1973 – the EEC as it then was – it had enough fish in its own waters and close by around the UK waters, that crews from here didn’t need to develop fishing sources elsewhere.

French and Spanish coasts go too deep to trawl in, he said, so those fishermen come to the continental shelf around Ireland, the UK and Iceland where the fish come to spawn.

“We’ve the jewel in the future of European waters: our fish, they come to spawn here, they go to the juvenile stage and they swim off to all the other countries.”

Our colleagues at Noteworthy are proposing to investigate the impact overfishing has had on the Irish fishing industry. See how you can support this project here> But now that the UK is leaving, it’s losing half of its fishing grounds because it only ever fished in its immediate area.

Irish crews fear that if there’s no deal on fisheries and the UK leaves the EU, the waters around Ireland will see even more traffic from Spanish, French and other European trawlers.

“If you look at all the other countries, the nomads we’ll call them, they came to Ireland and England. So, even though they lose [British] grounds, they can still come into Ireland’s grounds,” said Murphy.

“We’re going to see hundreds of boats coming in on top of us if we don’t get an agreement.

So we not only lose our other farm, we have to share the little one we have with everybody else, and we have the smallest share of fish in that farm. The French would have 10 times our monkfish quota in the Celtic Sea than we would. This latter point about quotas is made by other fishermen too – that when Ireland entered the EU, there was more of an emphasis on agriculture than on fish, and because of that fisheries “didn’t get as good a deal as we would have hoped”.

The UK had pushed for trade talks to be split into various sectors – with fisheries split out from other trade issues. But the EU has fought against that, and they are currently being negotiated as part of the one trade deal.

Murphy insisted a fisheries agreement must remain part of the trade talks agenda. Sean O’Donoghue, CEO of the Killybegs Fisherman’s Organisation in Co Donegal, agrees.

“If fisheries was split out from trade talks, we’re in really deep trouble,” O’Donoghue said, adding that if there isn’t a fisheries deal, there won’t be a trade deal.

RELATED READS:

John Ward is CEO of the Irish Fish Producers Organisation, which represents owners of trawlers and other commercial fishing vessels. He said that if Ireland loses access to UK waters, it would have “a tremendous negative effect on the Irish fishing fleet”.

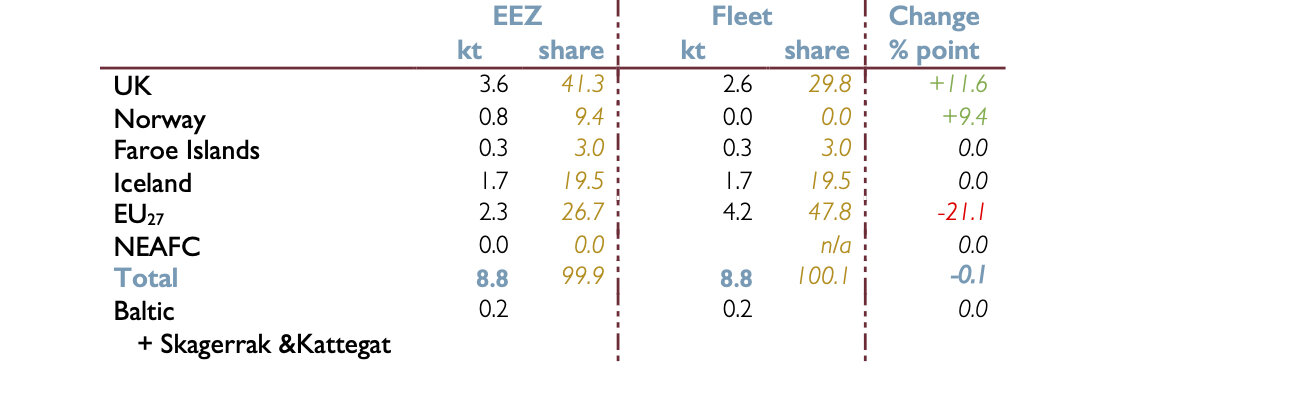

“Particularly for the two main species that we fish – being mackerel and prawns.”

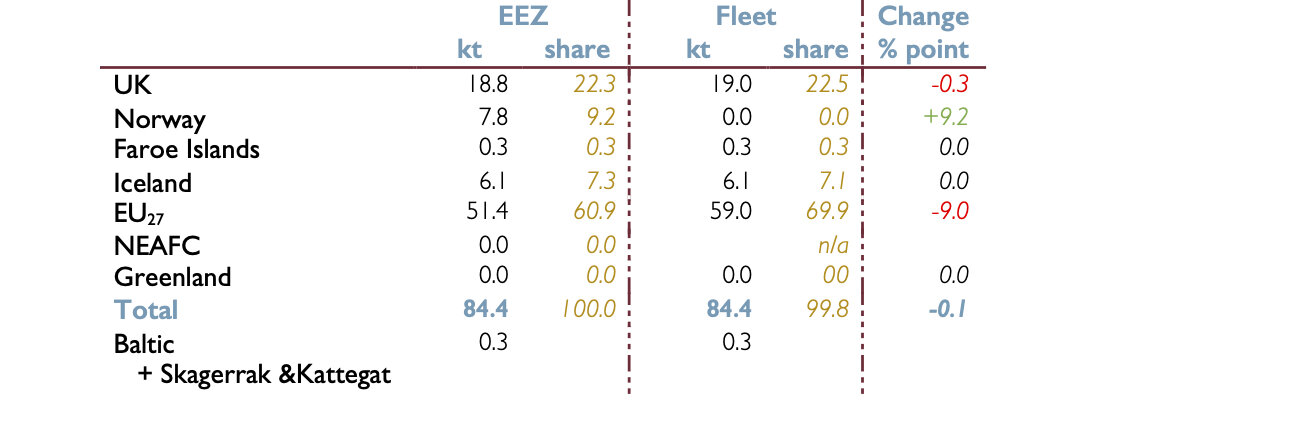

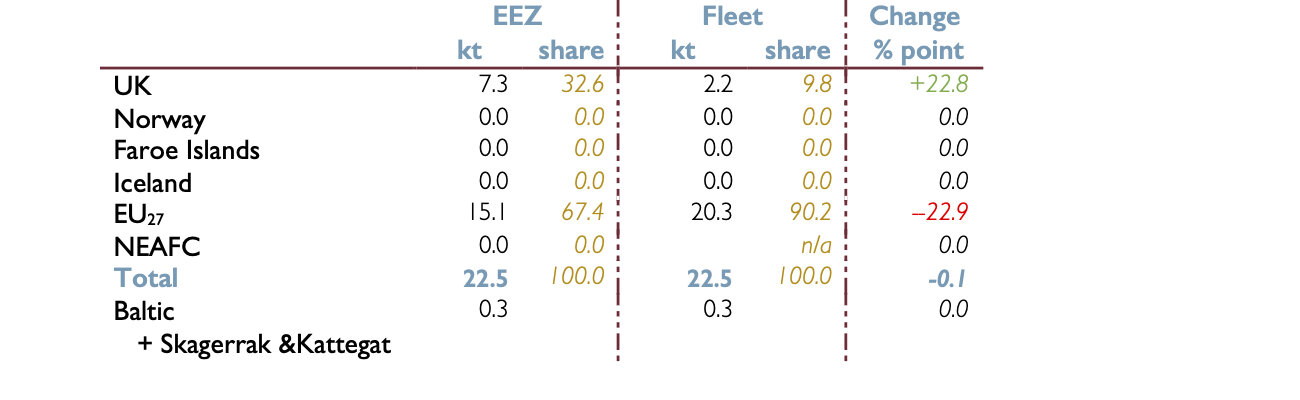

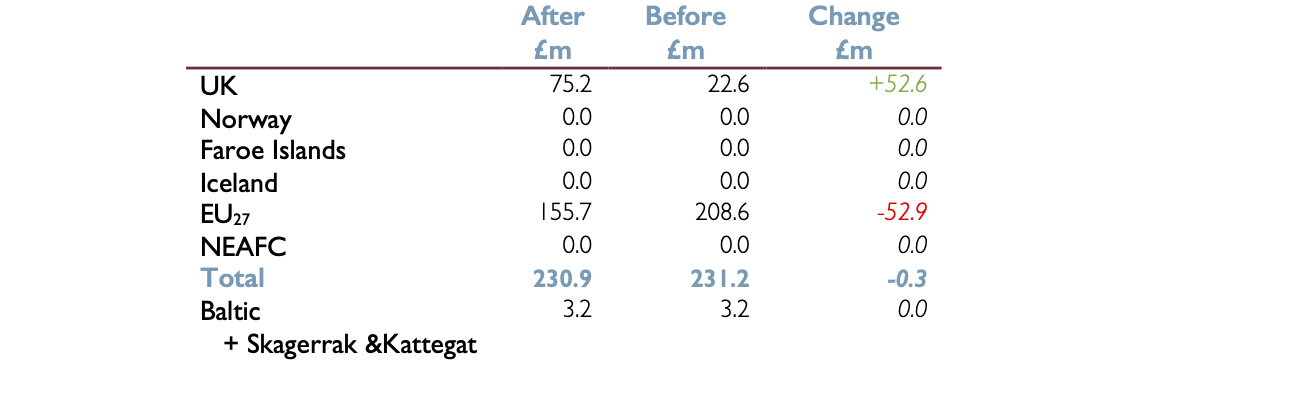

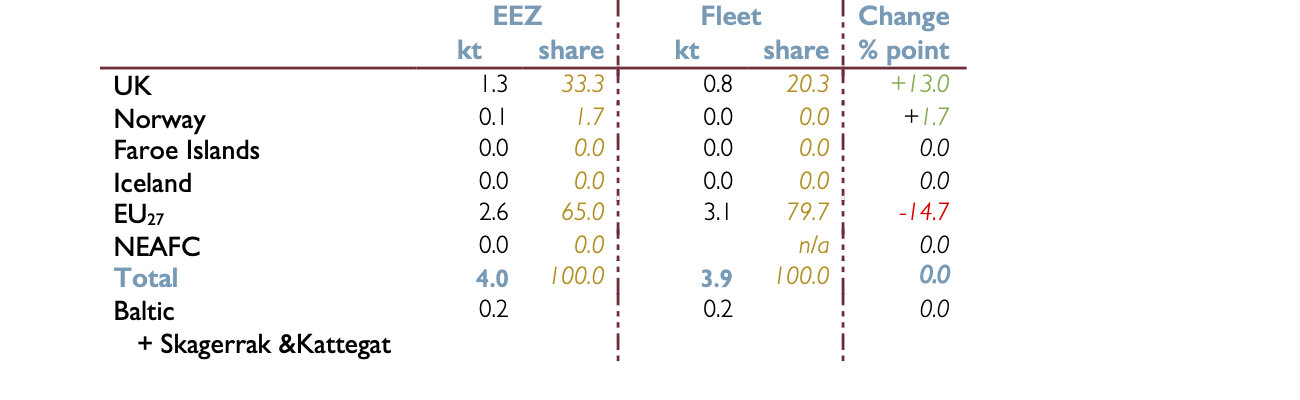

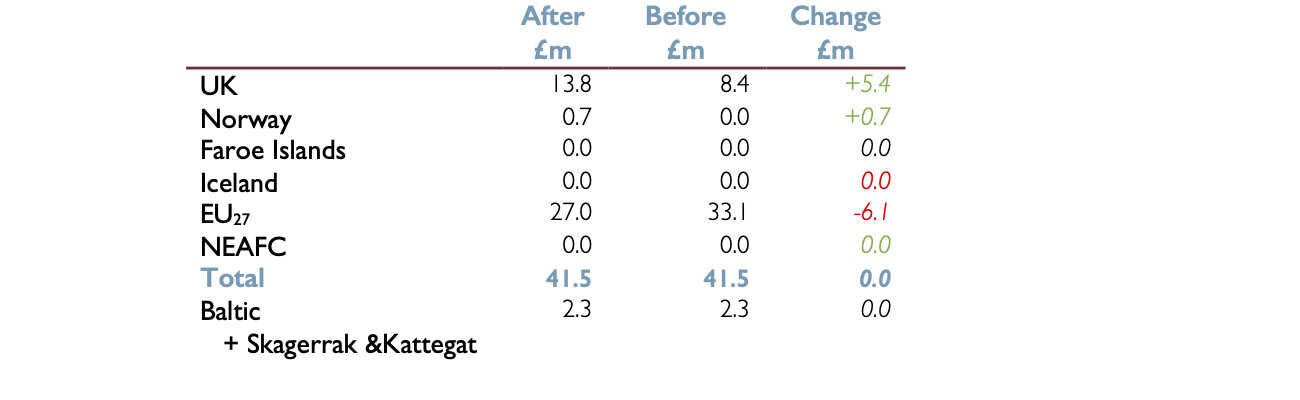

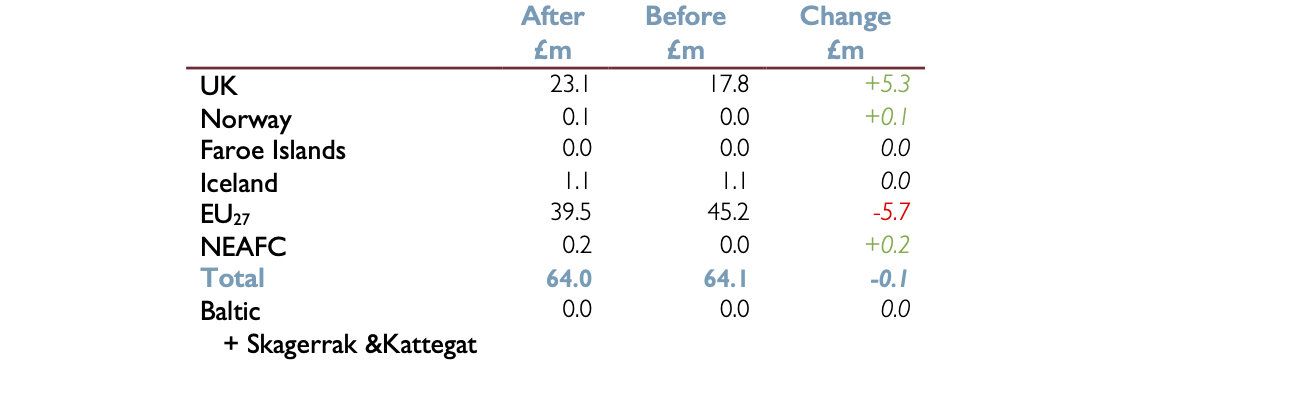

64% of Ireland’s largest fishery, mackerel, and 43% of our second biggest fishery, prawns, is caught in UK waters.

Mackerel migrate from the west coast of Norway, down the west coast of the UK, and the west coast of Ireland down to Biscay. They are available at different times and different areas, and we would fish a lot of our mackerel quota in UK waters.

O’Donoghue said that it would be “an unmitigated disaster for us”.

“If you look at it over 10 years, we’re over 60% dependent on catches of mackerel in the UK. We’re about 40% overall for all species. We share about over 50 species with the UK – the fish don’t recognise borders in the sea, as such.

The UK vessels do fish quite a bit in our waters, but we fish more in their waters than they do in ours.

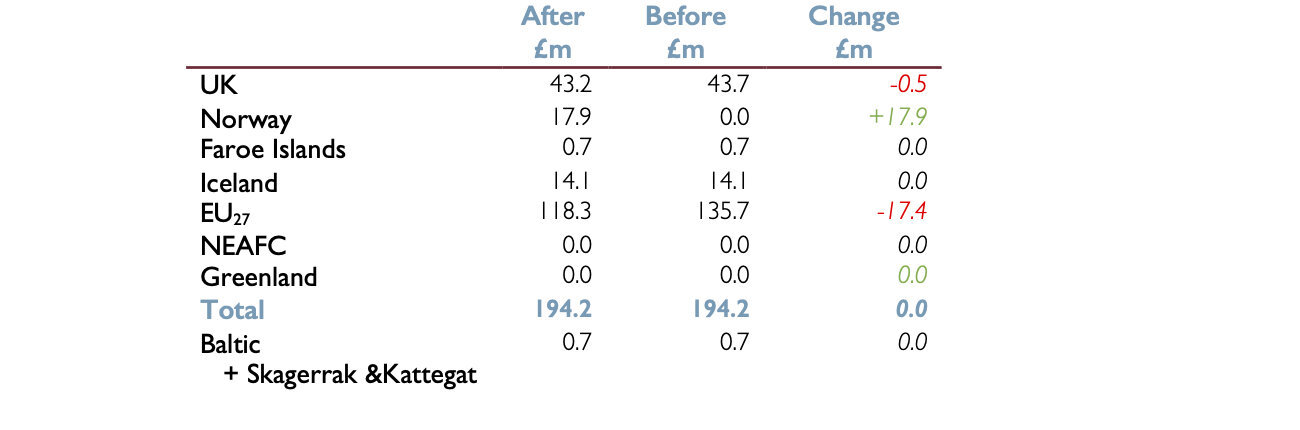

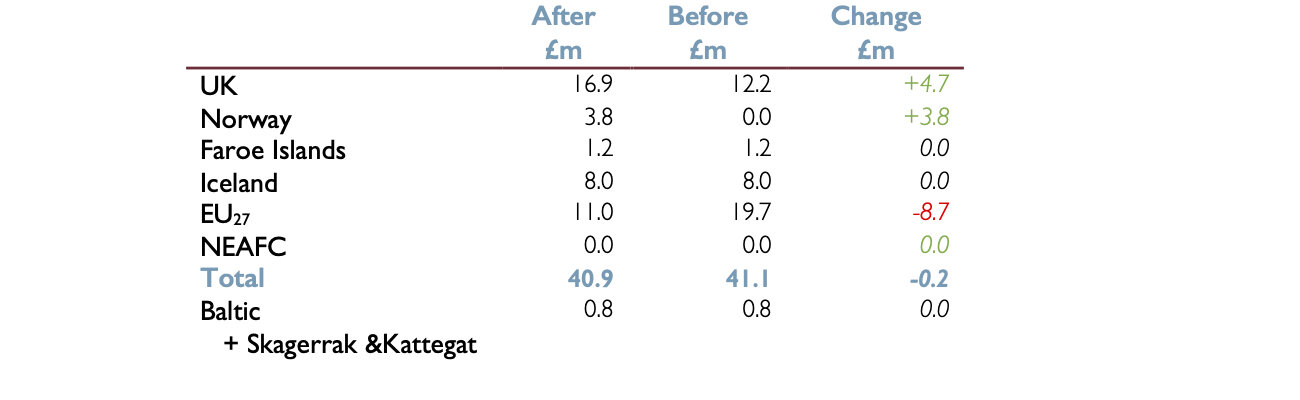

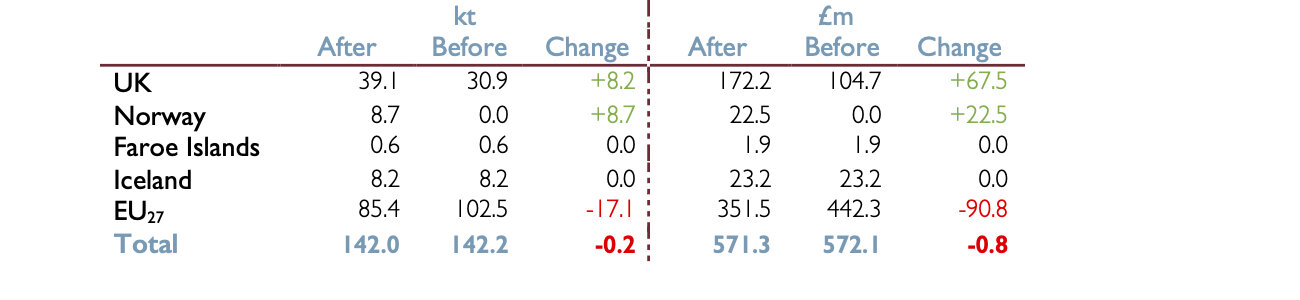

It would halve the size of the seafood sector, which is about €1.22 billion in value of the seafood industry. We would see that drop to €600 or 700 million of there was no deal for a long period of time. We would lose around 4,000 to 5,000 jobs of around 16,000 in the fishing industry [which includes ancillary services like production].

So what do fishermen want?

According to Murphy: “If you’re asking what do fishermen want, boil it down – we want to be protected.

“And the way we want to be protected … first of all we want the sustainability of the stock protected. We want to know how many boats are going to be allowed to come into Irish waters if the English kick them out. That’s first and foremost, it’s called displacement.”

Murphy is worried about an influx of boats coming in around Irish shores to fish there, and the danger that poses for the quality and sustainability of fish stock. It would be like hosting a football tournament, he says – but having all the teams play at once instead of one-on-one.

“So at the moment there’s a balance – boats fish all around the place, they have different ways of fishing. But if you condense them into one area, and they all keep running on the same grass at the same time, the grass won’t stand up. That’s nature. I think it’s the same for fishing.

“They want to keep the same [Common Fisheries Policy], even though the UK is taking away one third of the waters and one third of the fish out of the pot.”

Ireland’s waters represent around 20% of EU waters, and one third of the catch of fish, he says.

“England and Ireland would be the kingpins over the fishing industry in Europe if we had nobody else there. We would be the guys with the goldmines.”

This week marks the first face-to-face Brexit talks since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. They are being held in Brussels, with the level playing field request by the EU still proving to be the biggest stumbling block to agreeing a deal.

Negotiators have until the end of the year to reach an EU-UK trade deal; the UK had he option of requesting an extension, but have refused that option repeatedly. The deadline to avail of that offer was yesterday, 30 June.