Welcome to Through the Gaps, the UK fishing industry's most comprehensive information and image resource. Newlyn is England's largest fish market and where over 50 species are regularly landed from handline, trawl, net, ring net and pot vessels including #MSC Certified #Hake, #Cornish Sardine, handlined bass, pollack and mackerel. Art work, graphics and digital fishing industry images available from stock or on commission.

Monday, 29 June 2020

French fisherman fear losing access to British waters in Brexit talks.

He could probably catch fish in the bath!

Sunday, 28 June 2020

Weekend action in Newlyn.

Saturday, 27 June 2020

The food frontline: Richard Adams, fishmonger

We spoke to foodies on the frontline about what’s been going down.

Richard Adams works in his family business Trelawney Fish & Deli in Newlyn, Cornwall, alongside his brother Anthony and shop manager Andy Howes. In addition to their fish shop in the town, they also provide an overnight fresh fish mail order service for consumers and supply wholesalers that stock restaurants and small fishmongers across the UK.

How has lockdown affected your business?

We’ve seen a massive increase in demand for our overnight delivery service. I think it’s because people can’t go out to restaurants and are looking to treat themselves – plus they’re doing more cooking at home.

On the other side, there’s been a huge decrease in wholesale orders, so the direct to- consumer trade is helping us keep people employed. The wholesale business is starting to stabilise though; we’re now selling more fish to wholesalers that supply small fishmongers. People are getting used to the new normal and are using their local fishmonger more.

How have you adapted?

Our shop is still open but we can only have one customer in at a time. The biggest change is that the mail order element was just an add-on to the business, but we’ve now got a member of staff working on just that – and they’re flat out. We’ve even got a backlog of orders. Other businesses offer a set-price box and customers get what they’re given but we offer a bespoke service where people order over the phone and we advise on what’s best that day, so it’s time consuming.

Has the local community been supportive?

Definitely – the shop counter is still busy. The only thing we’re seeing a dip in is tourist trade.

What will you do after lockdown?

We’ll aim to maintain the level of overnight deliveries we’re doing. A lot of places in the country don’t have a fishmonger and many people didn’t know they could order fish by mail so I hope that after they’ve seen how good the quality, service and the price is, they’ll carry on ordering this way.

People may just return to their usual habits, but if we could do even 50 per cent of what we’re doing now, it would be good. It’s better for people to support fishmongers than supermarkets as fishmongers have more interest in the fishing industry – instead of just the bottom line.

Friday, 26 June 2020

The Lowlife of British fisheries

By Neil Stratton

THIS ARTICLE, the third in a series that considers – how fish landings might look if the major fleets fishing in the NE Atlantic landed a share of the overall harvest that matched the share taken from the corresponding EEZ – examines five species of flatfish: Plaice, Lemon Sole, Common Sole, Turbot and Megrims (strictly speaking, Megrims is a genus).

The first article included general notes about data sources, methodology and the caveat that the following analyses do not assume any particular form of fisheries agreement but merely provide an indication of how shares would change if such an agreement or agreements matched give to take. These continue to apply.

So, without further ado let’s start with Plaice.

PLAICE

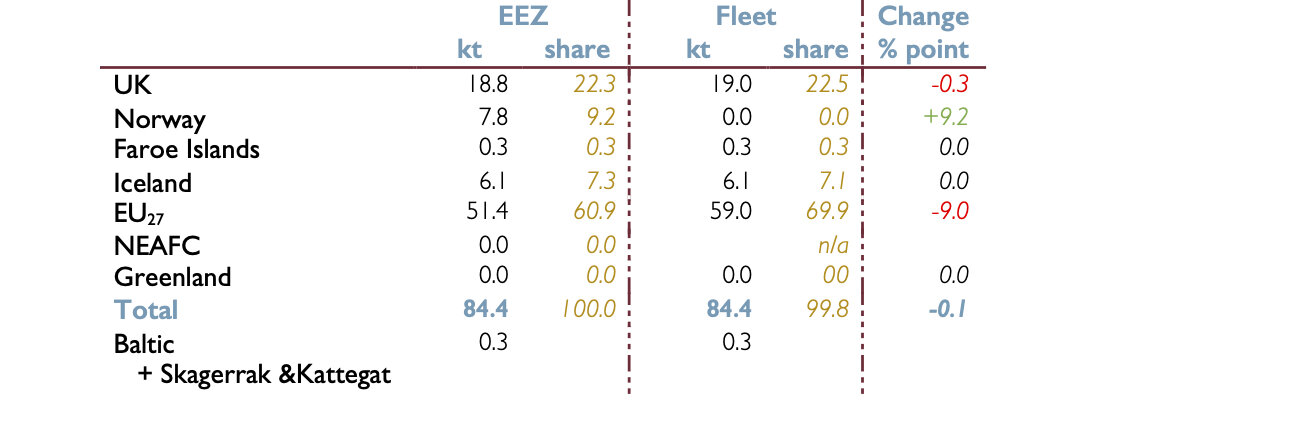

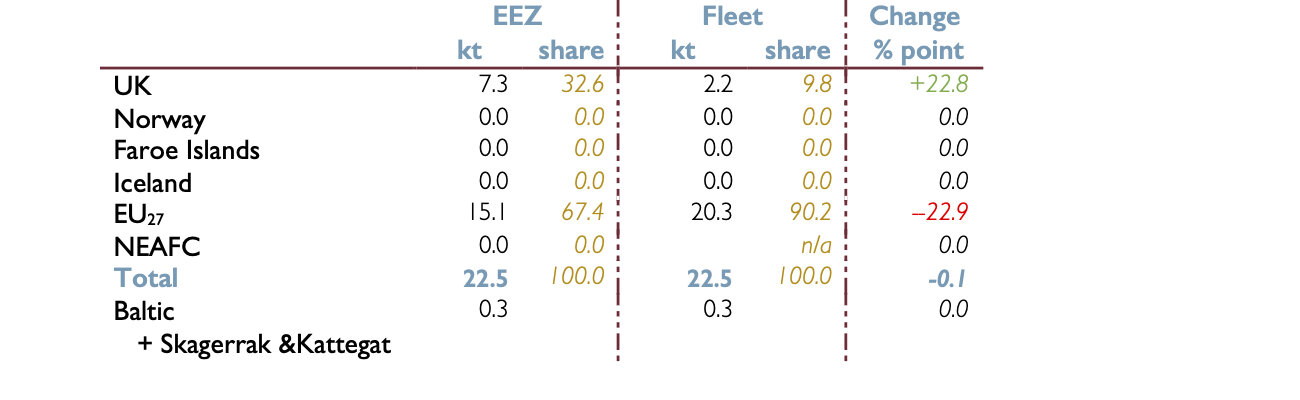

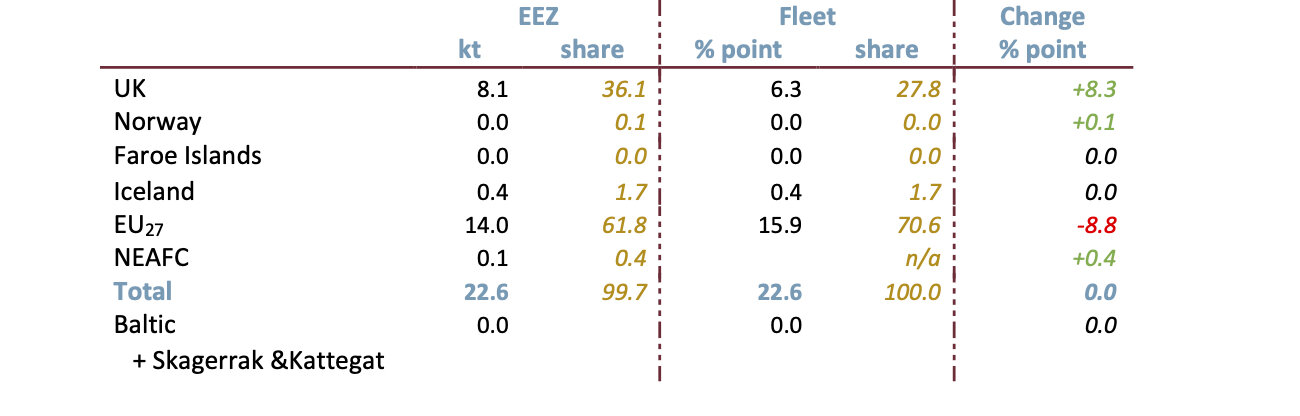

Table 1: Plaice landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

Faroe Islands: FI database does not specify location fish caught, all FI fleet landings assigned to FI EEZ. In reality some FI fleet landings might be from outside FI EZZ, in which case the FI EEZ figure will be lower and others correspondingly higher

The Norwegian database does not have separate entries for any flatfish other than Greenland Halibut.

The “Other flatfish” entry averages 8,768 tonnes for the years in question. Average catches from the Norwegian EEZ were 7,647 tonnes, 841 tonnes from the EU EEZ, 3 tonnes from FI and 1 from Icelandic EEZ

87% of Norwegian “Other flatfish” were landed from the Norwegian EEZ, 9.6% from the EU EEZ and virtually none from the FI and Icelandic EEZs

The species breakdown is unknown but this entry sets a ceiling for possible Norwegian fleet landings of 8.8 kt, with 7.6 kt from the Norwegian EEZ and 0.8 from the EU. In reality, since this entry includes a number of species, the figure for any individual species, such the five considered in this article, would be substantially lower.

The above notes regarding the Norwegian database apply to all five species in this article.

NEAFC: in reality landings from NEAFC would be landed by a national fleet but which fleet would be by agreement between parties to NEAFC. UK currently party to NEAFC through membership of EU. Post EU departure?

Plaice is the flatfish caught in the greatest quantities but it is also a relatively low value one. Over half of the Plaice landed from the NE Atlantic is landed from the EU27 EEZ. Nevertheless, the quotas allocated to the EU27 have allowed it to land more than its share of the resource.

If some of the 841 tonnes of ‘Other flatfish’ landed by the Norwegian fleet from the EU EEZ was Plaice then not only would Norwegian fleet landings and share not be zero but the landings and shares from other EEZs would be increased and the consequent reduction in UK and EU27 landings and shares would be correspondingly reduced.

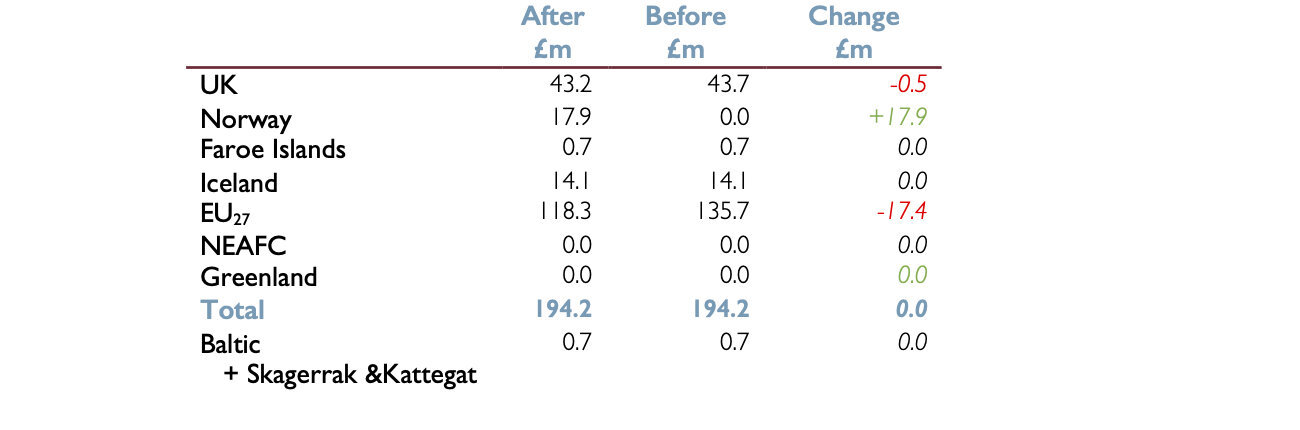

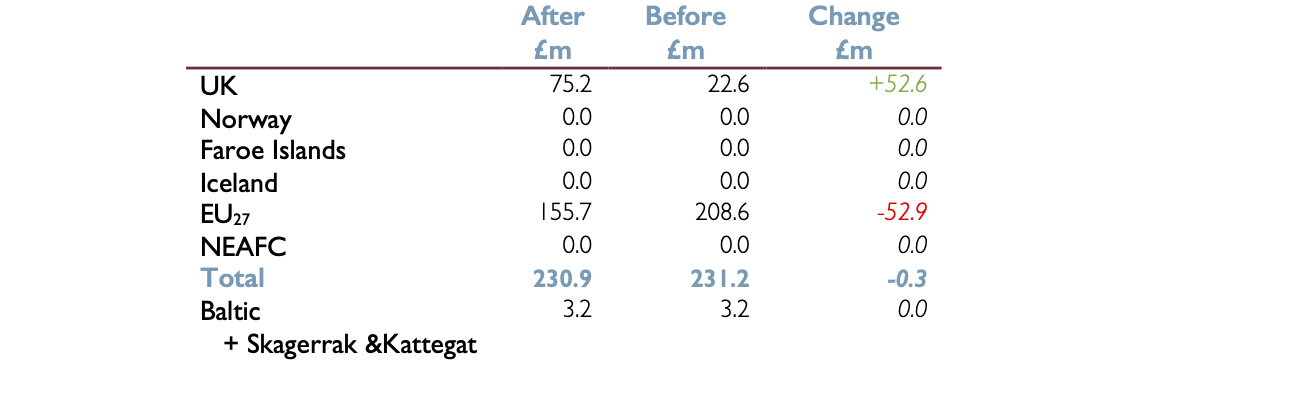

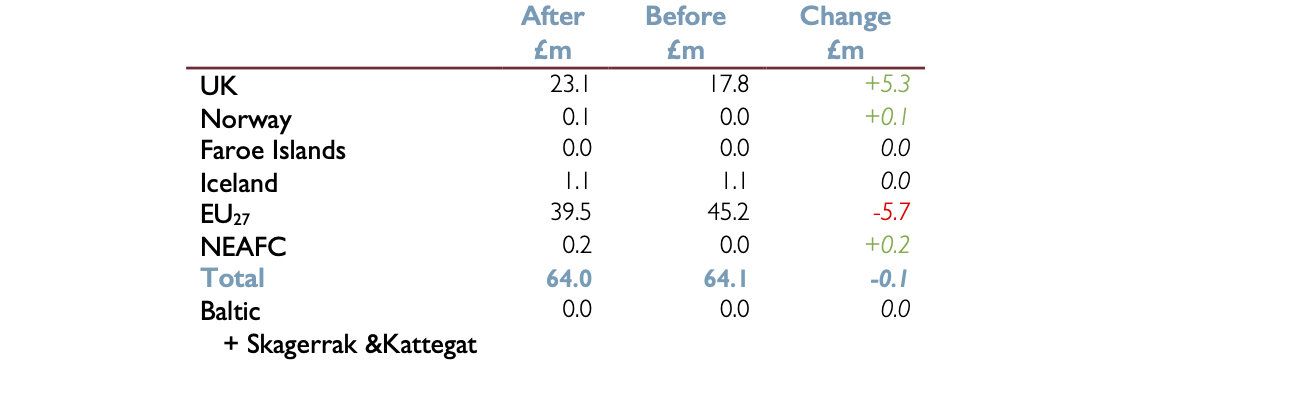

Table 2: Value of Plaice landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

Before and after a possible redistribution @ £1,820.00 /tonne

LEMON SOLE

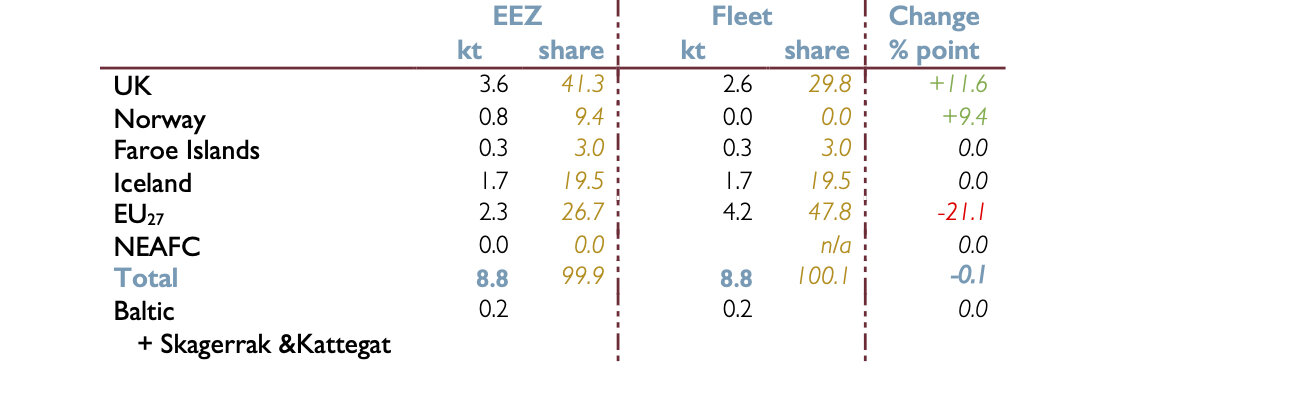

Table 3: Lemon Sole landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

See note on Norwegian database in Plaice entry.

Faroe Islands: FI database does not specify location fish caught, all FI fleet landings assigned to FI EEZ. In reality some FI fleet landings might be from outside FI EZZ, in which case the FI EEZ figure will be lower and others correspondingly high.

Landed in much smaller quantities than Plaice, but higher in value, Lemon Sole is another species for which the EU27 has awarded itself a disproportionate share. A redistribution based on resource share would see the UK and the EU27swap places in terms of Lemon Sole landings.

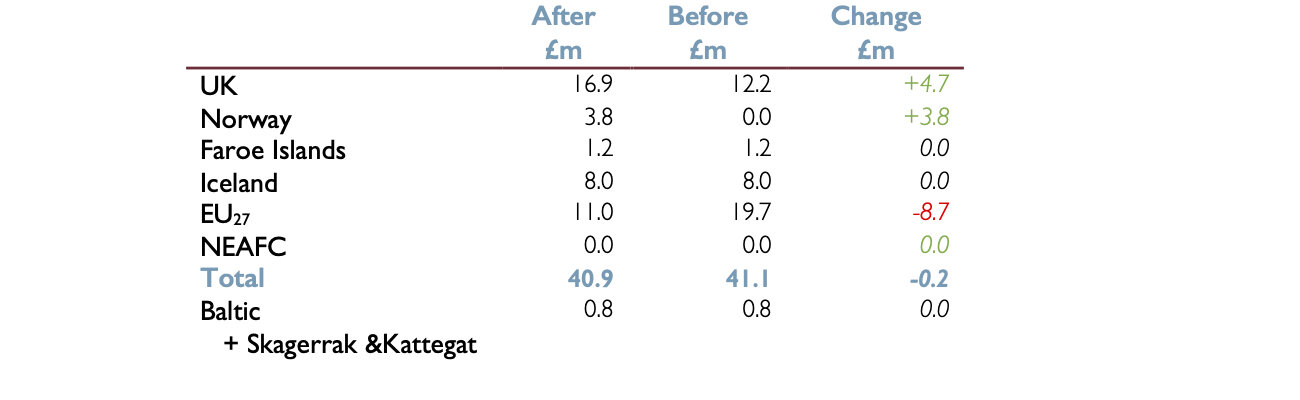

Table 4: Value of Lemon Sole landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

Before and after a possible redistribution @ £4,707.00 /tonne

COMMON SOLE

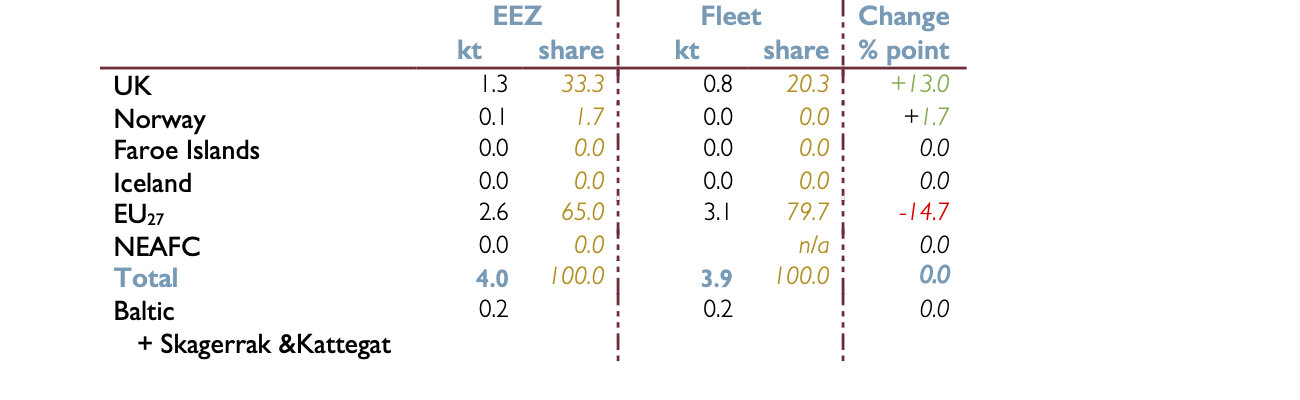

Table 5: Common Sole landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

See note on Norwegian database in Plaice entry.

The Icelandic and Faroe Islands databases do not have a separate entry for Common Sole. In the case of Iceland, there is an “Other flatfish” entry. This average 222 tonnes for the years in question; all landed from the Icelandic EEZ. Icelandic landings would therefore have no impact on the redistribution.

The Faroe Islands has no “Other flatfish” entry but it does have an “Other” fish entry, this averages 2,088.9 tonnes for the years for which FI figures are available. FI Common Sole landings could not therefore exceed 2.1 kt; in reality they are likely to be much less.

EU27 and UK landings of Common Sole from the FI and Norwegian EEZs are close to zero and are zero for the Icelandic EEZ; this coupled with the lack of separate entries in the Norwegian and FI databases suggests FI and Norwegian landings are ‘modest’.

It is not therefore possible to model how landings might be redistributed for all NE Atlantic fleets and EEZs and the above table really looks at just the UK and the EU27.

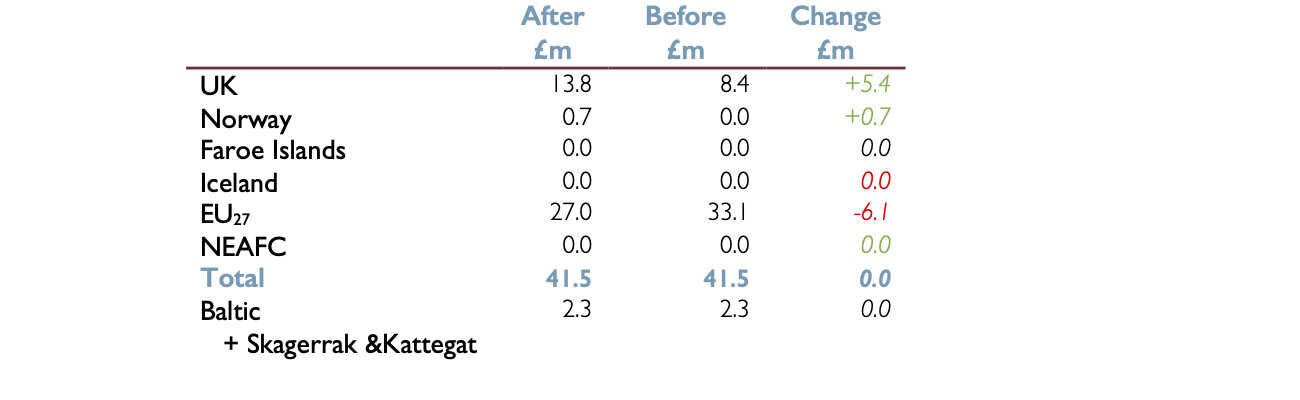

Roughly two thirds of Common Sole are landed are landed from the EU27, which means that post-redistribution the EU27 continues to land the bulk of Common Sole in the NE Atlantic. However, the UK receives substantial additional share (22.8 percentage points) to take its share from just 9.8% to the 32.6% landed from its EEZ; and this increase in share combined with absolute quantities that are several times those for Lemon Sole and a value that is getting on for six times that of Plaice means the potential gain to the UK is in excess of £50 million.

Table 6: Value of Common Sole landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

Before and after a possible redistribution @ £10,295.00 /tonne

TURBOT

Table 7: Turbot landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

See note on Norwegian database in Plaice entry.

The Icelandic and Faroe Islands databases do not have a separate entry for Turbot either. In the case of Iceland, there is an “Other flatfish” entry. This average 222 tonnes for the years in question; all landed from the Icelandic EEZ. Icelandic landings would therefore have no impact on the redistribution.

The Faroe Islands has no “Other flatfish” entry but it does have an “Other” fish entry, this averages 2,088.9 tonnes for the years for which FI figures are available. FI Turbot landings could not therefore exceed 2.1 kt; in reality they are likely to be much less.

EU27 and UK landings of Turbot from the FI and Norwegian EEZs are close to zero and are zero for the Icelandic EEZ; this coupled with the lack of separate entries in the Norwegian and FI databases suggests FI and Norwegian landings are ‘modest’.

It is not therefore possible to model how landings might be redistributed for all NE Atlantic fleets and EEZs and the above table really looks at just the UK and the EU27

Another species where a redistribution based on resource share would result in the UK receiving substantial additional share, although the EU27 EEZ would continue to be the dominant source of Turbot and its fleet would continue to land the bulk of the catch, albeit not a disproportionate share as at present.

Although the absolute tonnages of Turbot landed are small and the UK’s potential gain is just 0.5 kt, the high value of Turbot means that even half a kilotonne still yields an extra £5 million.

Table 8: Value of Turbot landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

Before and after a possible redistribution @ £10,513.00/tonne

MEGRIMS

Table 9: Megrims landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

See note on Norwegian database in Plaice entry.

The Faroe Islands database does not have a separate entry for Megrims either. The Faroe Islands has no “Other flatfish” entry but it does have an “Other” fish entry, this averages 2,088.9 tonnes for the years for which FI figures are available. FI Megrims landings could not therefore exceed 2.1 kt; in reality they are likely to be much less.

EU27 and UK landings of Megrims from the FI and Norwegian EEZs are close to zero and are zero for the Icelandic EEZ; this coupled with the lack of separate entries in the Norwegian and FI databases suggests FI and Norwegian landings are ‘modest’.

It is not therefore possible to model how landings might be redistributed for all NE Atlantic fleets and EEZs and the above table really looks at just the UK and the EU27

Landed in similar quantities to Lemon Sole but closer in value to Plaice, Megrim is another flatfish that is mainly landed from the EU27 EEZ but for which the UK’s current quotas does not reflect its share of the resource. Following a redistribution, UK landings might rise by a little over a quarter (8.3 percentage points) and bring in another £5 million.

Table 10: Value of Megrims landings from the NE Atlantic by EEZ and fleet

Before and after a possible redistribution @ £2,833.00 /tonne*

*Defra 2017 prices

SUMMARY

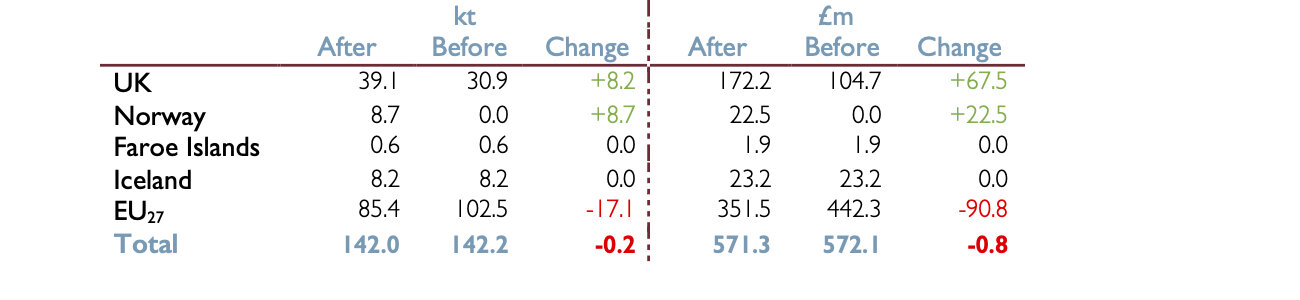

To sum up the potential changes for these five species, Table 11 presents the overall tonnages and values of landings and how they might change if overall landings in future matched the average for 2010-16.

This assumption might well of course not hold good; and there are further uncertainties given the absence of data for some species and countries, the lack of geographical precision of some databases, how landings from international waters might be handled and the arbitrary use of UK 2018 prices as the basis for values, as has been highlighted above in the small print. Table 11 should therefore be viewed as an indicator of the direction of travel rather than a precise forecast.

Table 11: Summary

See note on Norwegian database in Plaice entry.

Note, the apparent overall loss of tonnage and value is more apparent than real, and relates to landings from NEAFC regulated international waters. In reality these fish would be landed; the question is by whom.

Flatfish are the EU27’s strong suit, with the EU27 EEZ accounting for roughly 60% of NE Atlantic landings of these five species. Nevertheless, as a result of the fact that EU27 landings during the period being considered were well in excess of its share of the resource, even here the EU27’s share would fall back following a redistribution.

Only 1 kilotonne of these five species is landed from the private EU27 lake that is the Baltic, Skagerrak and Baltic, so the EU27 would not be able to turn to it to buffer the impact of reduced share in the NE Atlantic.

Although the tonnages involved are much lower than for the species considered in the previous two articles, the high value of Common Sole and the extent to which the UK’s share would be adjusted means that the financial gain to the UK resulting from a redistribution of fishing opportunities for these five species exceeds that for the previous five.

Subscribe to our tea-time newsletter here, and follow us on Twitter here and facebook here.

After a first degree in zoology followed by research in developmental genetics, Neil Stratton worked for a number of European publishers before beginning an analysis of European fish landings with the think tank EH99 in the spring of 2018. The recently published report Fair Shares for All is based on this analysis.

Tuesday, 23 June 2020

Cornish Sardine season to start soon!

Government suffers heavy defeat on post-Brexit fishing policy as Lords push for more environmental protection

The Bill enables the UK to become an independent coastal state post-Brexit, with foreign fishing boats barred from fishing in UK waters unless licensed to do so. But independent crossbencher Lord Krebs said that, as currently drafted, it did not guarantee the protection of fish stocks and the wider marine environment.

Take back control: A fisherman protests against an earlier Brexit withdrawal agreement(PA) To be absolutely sure the Bill “does what it claims to say on the tin, let’s get the commitment to protecting the natural environment written into it,” he said. Lord Krebs, a former chairman of the Food Standards Agency, said whenever there was a trade-off between short-term economic and employment considerations and long-term environmental sustainability, short-term factors nearly always won.

But Environment, Food and Rural Affairs minister Lord Gardiner of Kimble warned the amendment would undermine the Bill’s carefully balanced approach to sustainability. Lord Gardiner said peers were all seeking the same thing – a “vibrant and sustainable fishing industry with a greatly improved marine environment”.

The industry could only be viable if it was environmentally sustainable and this was why the Bill gave equal weight to environmental, social and economic considerations, he added. He said the amendment would create a “hierarchy” of objectives and mean that in any circumstances “short-term environmental considerations would need to override even critical economic and social needs”.

Sunday, 21 June 2020

A Path to a New Fisheries Management Agreement Between the EU and the UK

When the transitional fisheries provisions come to an end, some of the richest fishing grounds that have been managed under the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) will instead be managed by the UK because they fall within the nation’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). A new joint management framework will be required for around 100 stocks shared by the UK and the EU. In addition, the parties will need to update arrangements with the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, Norway and Russia, none of which are EU members.

In their 2013 reform of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy, member states—including the UK—committed to ending overfishing by 2015 where possible and 2020 at the latest. More recently, the EU has bolstered its wider environmental commitments with the publication of its European Green Deal. Meanwhile, the UK government has said it wants to become a “world leader” in fisheries management following its departure from the EU.

The negotiations now underway on a joint fisheries management framework offer a chance for both parties to adhere to the sustainability commitments they have made and demonstrate that they have learned the lessons from good and bad fisheries management around the globe. Moving further towards sustainable stewardship of these shared fish stocks, many of which are still being overfished, will provide more productive fisheries, more jobs, and better ecosystem resilience in the face of climate change and other threats.

Principles for successful fisheries management Following these 10 proposed principles will ensure a solid foundation towards achieving sustainable and successful fisheries in Europe post-Brexit. In implementing the principles, the EU, the UK and the other coastal states involved in Northeast Atlantic fisheries should formally set the basis for future fisheries management cooperation in conventions, agreements, and memoranda of understanding. These arrangements on equitable resource management—including those for the transition—must be binding and reflect each party’s interest in shared fisheries, while maintaining a sharp focus on sustainability.

The objectives for joint fisheries management must include provisions regarding abundance of fish populations, limit reference points for mortality, and precautionary and ecosystem considerations. In addition to objectives to maximise yield in the long term, coastal states must act with urgency to conserve biodiversity, considering the impact of fishing activity on both fish populations and on the whole ecosystem.

This requires integrating other policy objectives and processes into fisheries management. That would ensure fisheries’ decisions contribute to ecological recovery, protect vulnerable species, maintain ecosystem structure and functions, and promote resilience in the face of other threats to the marine environment, such as climate change. Management under an EU-UK framework agreement must implement a genuine precautionary approach as defined by the United Nations Fish Stock Agreement2 (UNFSA). When the available data and information are uncertain, unreliable or inadequate, decision makers should engage in more cautious management.

The absence of adequate scientific information cannot be used as a rationale to postpone or fail to take conservation and management measures. In particular, decisions on fisheries measures should aim to bolster the resilience of fish stocks and ecosystem functioning to withstand climate-related changes and be based on the most recent scientific methods and models for dealing with risk and uncertainty, as required by the UNFSA. The EU and the UK should demonstrate ambitious leadership and foster a “race to the top” in settingtheir purposes and goals, using the most robust approaches as a baseline for all to follow.

The shift to a new system of shared management must be seized as an opportunity for upgrading the conservation and sustainability objectives that drive current management in European waters and beyond. The objectives of the EU’s CFP should constitute a baseline from which to build. The EU and the UK’s responsibilities for conservation and sustainable joint management of fish populations must take priority over other issues in the negotiations on fisheries.

The new framework must deliver sustainable stock management for the long term, and not be dependent on the status of negotiations on issues such as trade of fish products or levels of reciprocal access to specific waters. The framework agreement for fisheries management should strive for balance and fairness, respecting the obligations and rights of coastal states that were set out in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea3 (UNCLOS) and in the UNFSA.

Existing international agreements set out objectives and obligations for equitable joint management and dispute resolution, not just technical fisheries aims. These provisions should be reflected in the new framework for cooperation designed by the EU and the UK. Multi-annual management should be the underlying approach by default.

Although details will need to be revisited regularly, all stakeholders benefit from agreeing to and working towards long-term sustainable management objectives. That includes stable sharing arrangements, predictable and automatic harvest strategies, a robust monitoring and evaluation scheme, a periodic review process, and any necessary mechanisms to transition from previous arrangements to a new system. Talks on joint management should be comprehensive, including all relevant coastal states and stakeholders, and unilateral decision-making processes on shared stocks should be avoided.

In line with UNCLOS requirements, collaboration on management must be multilateral when more than two coastal states have a stake in a given fish population or fishery in order to ensure transparency across all relevant states. The role of regional fisheries management organisations such as the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission must be considered in this context. The EU, the UK and other coastal states should set explicit standards for the scientific advice on which decisions will be made, using the best available peer-reviewed advice from independent institutions recognised at the international level.

Published scientific advice from independent scientific institutions such as the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) should be used as the basis for management, rather than unpublished or lastminute submissions from individual states. The new framework should be consistent with the obligations and rights under the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters4. Management proposals, negotiations and decisions should be made transparently, with access guaranteed for all stakeholders, including the fishing industry, civil society organisations and other interested parties.

This means the involvement of all concerned stakeholders in the development of proposals, participation in meetings where decisions are made, and accountability for those making the decisions through clear responsibilities and communication with all interested parties. Citizens of the EU and the UK—and those of other coastal states involved in the shared fishery— must be able to scrutinise management decisions.

Management objectives and all other elements of negotiated harvest strategies and annual decisions must be clear and available to the public. The joint management measures, the scientific advice underpinning them and the positions of the different parties involved must be made available to those interested in reviewing them. Conclusion The negotiations on a joint framework for management of fisheries shared by the EU and UK offer an opportunity to deliver on the policy goals that both parties agree are important: sustainable fisheries that provide food, jobs, and a future for the fishing industry, while safeguarding fish populations and the resilience of the marine environment.

These sustainability aims, lauded by both sides, can be achieved only if objectives, strategies and policy tools are based on the best available science. In addition, decision makers must apply a precautionary, long-term approach that draws from best practice in fisheries management worldwide. Successful joint management also will depend on transparency regarding aims and outcomes, the participation of all stakeholders in decisions, and ambitious leadership that puts sustainability at the heart of fisheries management.

Endnotes European Union, “Agreement on the Withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community,” Official Journal of the European Union (2019): 1–177, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12019W/TXT(02)&from=EN.

United Nations Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (1995),

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982),

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention) (1998), https://www.unece.org/env/pp/treatytext.html.