With 2020 just around the corner, we’ve reached the deadline set in the reformed Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) to end overfishing. Due to years of delay in which fishing ministers set fishing quota – quantity limits on the amount of fish that can be caught – above scientific advice, dramatic cuts to fishing quotas are now inevitable. The opportunity for early action has been lost, but the power is in the hands of fishing ministers and their national governments to secure good livelihoods for fishers despite the necessary reductions. Indeed, there are lessons here for setting ambitious policy deadlines – and sticking to them – in delivering a just transition.

|

| MSC Cornish sardines - sustainable fishing. |

For decades, ministers have been trapped by the logic that higher limits mean more fishing – although often for one year only. The result is a cycle of scientific advice for quota reductions, fishing limits set too high, continued overfishing, fish populations in poor condition, and the annual cycle repeats with a loss of jobs in each rotation. As fishing ministers change posts over time this short-termist logic may be ‘rational’ for their own political calculus but it is the health of fish and fishing communities that bear the consequences in the long run.

For the fishing industry, research has consistently revealed that ending overfishing has larger economic benefits the sooner it is achieved. This is because if you fish less now, fish populations grow in size, reproduce more, and there is a greater population that can support larger catches. Or looked at in terms of an investment, EU fishing ministers are ‘paying’ interest rates of 10 to 200% (depending on the species) by legislating for fishing today at the loss of what could be fished in the future.

What makes this situation even more irresponsible is that since the 2013 CFP reform secured the 2020 deadline, there have been plenty of opportunities for fishing ministers to transition to sustainable fisheries with minimal impact on fishers. When fuel prices dramatically fell at the end of 2014, fishing costs decreased and profits rose providing a buffer against any impact from quota reductions. As we advised, “rather than treating lower fishing costs as a simple windfall gain, this opportunity could be used to make a final push to end overfishing in Europe and achieve long-term sustainability with no significant hit to economic viability in the short-term.” This unnecessary delay also creates a precedent in how other policies are expected to be properly implemented, with repercussions and a ‘moral hazard’ across all other policy areas.

We have now reached the endpoint with the first quota negotiations scheduled in October for the Baltic Sea and December for the North Sea and Northeast Atlantic. “You may delay,” Benjamin Franklin wrote, “but time will not.”

ENSURING A JUST TRANSITION

At the same time, just as it is irresponsible to delay quota cuts until the very end of a transition period, it is also irresponsible to make these cuts with no regard for the consequences. There are livelihoods at risk and many coastal communities are intimately tied to the fortunes of the fishing industry. So, what can governments do?

What follows is specific to fishing policy, but behind these ideas are some core principles for doing any kind of just transition policy well: mitigate the effects for the most vulnerable; design social policies that can guard against wage or job losses; and state investment.

1. Use quota allocation to change the distribution of impacts

Frequently lost in the discussion over the size of the pie (the total amount of fishing quota), is the issue of distribution. It is up to each EU Member State to decide how quota is divided amongst their fishing vessels.

Fishing quota is a public resource and access to it should never just be given out indiscriminately, particularly not when quota reductions need to be made. There are countless reasons why quota should be distributed differently. That the initial quotas were gifted decades ago to those overfishing the most at the time, the economic vulnerability of some fleets and high profits in others, or the principle that quota distribution should be based on value that is generated or lost, for example value is generated when catches are landed locally or lost when a fishing fleet damages the seabed.

One policy we could learn from to buffer quota reductions is the Norwegian ‘trawler ladder’. Under this policy, the division of cod quota between the Norwegian coastal fleet of smaller vessels and the trawler fleet of larger vessels depends on the overall quota. When the quota is low, the coastal fleet receives a higher proportion to protect against going completely bust, whereas when quota is high the trawler fleet gets a larger share more in line with catch history. While ministers may have you believe otherwise, any EU Member State could implement an identical policy.

2. Use labour policy to change how fishers are paid

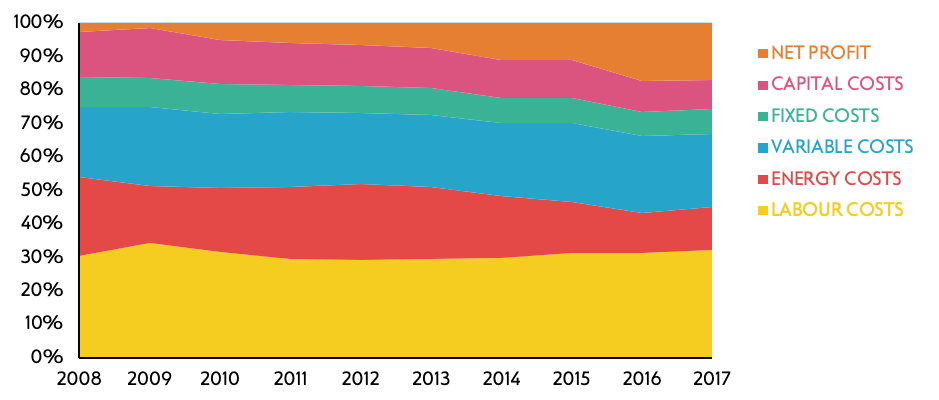

Vulnerability is not just felt differently between businesses but also within them. Despite its long history, working as a fisher displays all the uncertain features of the modern gig economy. Across EU Member States fishers tend to be paid through a share of vessel earnings – a ‘crew share’. This means that wages increase as catches increase, but the reverse is also true and a bad fishing trip could mean very little or no income at all. Another feature of this payment system is that while vessel income has remained stable, savings made on decreasing fishing costs (e.g fuel price decrease and lower rates on loans) have accumulated in the form of higher profits (orange) for vessels, rather than paid out as wages (yellow) as illustrated in the figure below.

|

| Figure: Cost components and profit as a percentage of fishing incomeSource: STECF – The 2019 Annual Economic Report of the EU Fishing Fleet |

Must this be the case? Of course not. We can change the rules of how the economy should operate. In 2003 Belgium passed a law to guarantee income security for each trip and the country now has crew wages nearly double any other EU Member State. Policies like this that look after income security must be on the table to ensure good livelihoods.

3. Use fisheries subsidies to fund the transition

A third area of policy to utilise is the direct role of the state to invest in the long-term sustainability of the industry and this is particularly necessary at a time of quota reductions. There is already billions set aside for fisheries through the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund. Member States have the option to directly subsidise incomes when fisheries are closed, but even beyond this there are investments that respect and utilise the experience of fishers; with skills at sea and a huge gap in our understanding about our marine ecosystems the programmes practically write themselves.

All three of these policy approaches lie in the hands of EU Members States. Fishing ministers – and their predecessors – have harmed EU fisheries by setting quotas too high over the past decades and holding back populations’ recovery, but Member States can make things right by recognising the power they have to not just set the size of fishing quotas, but determine how the impacts are felt. We cannot implement policies inhumanely, just as we cannot ignore the ambitious deadlines we agree upon.

Post courtesy of Griffin Carpenter senior research fellow at New Economics Foundation.